Torbjørn “Thor” Pedersen is on a mission to visit every country in the world in a single journey, without taking a single flight.

After roughly six and a half years on the road and a budget of US$20 a day, Pedersen is just nine countries away from reaching this goal.

There’s only one problem: He’s stuck in Hong Kong.

While the 41-year-old was waiting in the city to board a ship to his next stop, the Paclfic archipelago of Palau, the outbreak of COVID-19 and ensuing travel restrictions derailed his plans.

But the Danish native and goodwill ambassador for the Danish Red Cross is determined to make the most of the situation.

He’s been spending his days tackling Hong Kong’s many hiking trails, working with the local Red Cross society, giving motivational speeches and updating his blog, Once Upon a Saga, where he has been chronicling his adventures.

When I meet Pedersen for tea at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Hong Kong, he looks surprisingly bright-eyed for someone who’s been in transit for more than six years.

The 41-year-old, who sports road-worn Black Salomon X Ultra trekking trainers and a chest-length beard, is clearly itching to keep moving.

“Every day I spend in Hong Kong is another day that I’m not making progress. I’m losing time but trying to make the best of it,” Pedersen tells CNN Travel.

“With what’s going on in the world, it will take at least another year to finish. Quitting is a consideration — I’m dead tired [of traveling] and ready to go home. But I’m also stubborn and driven.”

Born in Denmark, Pedersen had an international upbringing where he always had “one leg in Denmark and one leg somewhere else.”

During his childhood, his family flitted between Toronto, Vancouver and New Jersey for his father’s job in the textile industry and visited his mother’s side of the family in Finland during summer and winter holidays.

“My mother is a travel guide, so she speaks several languages and has always been interested in the world,” he adds.

“When it comes to a sense for business and structure, getting up early and getting things done, I got that from my father. I got walking around in the forest looking for mushrooms and trolls, thinking outside of the box and being adventurous from my mother.”

As an adult, Pedersen served in the Danish Army as a Royal Life Guard (akin to the fur-capped Queen’s Guard at Buckingham Palace in London) then worked in the shipping and logistics industry for 12 years, where assignments took him from Libya to Bangladesh, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Greenland and Florida.

The idea to attempt this particular challenge — to visit every country on a nonstop journey without taking a single flight — came to him serendipitously, through an article his father sent him.

“I discovered that it’s actually possible to go to every country in the world — I had never thought about it before,” says Pedersen.

Six years away from home

Nine countries to go: Pedersen began traveling in October 2013. After roughly 6.5 years on the road and a budget of US$20 a day, Pedersen is just nine countries away from reaching his goal.

Torbjørn (Thor) Pedersen/Once Upon A Saga

After 10 months of careful planning, Pedersen departed on October 10, 2013.

First, he’d travel around Europe, then North America, South America, the Caribbean, Africa, the Mediterranean, Middle East, Eastern Europe, Asia and over to the far-flung islands in the Pacific.

“Since I worked in shipping and logistics, I was used to having multiple things in the air at the same time, finding solutions and making everything more efficient,” he says. “That helped a lot in a project like this — it could easily take 20 years if you’re not careful.”

There are 195 sovereign nations in the world, according to the United Nations, but Pedersen isn’t stopping there. By the end of his journey, he will have visited 203 countries in total.

Pedersen imposed exceptionally strict rules on himself: He must spend at least 24 hours in every country and can’t return home until he’s done.

In addition, Pedersen planned to visit the Red Cross (also known as Red Crescent or Red Crystal, depending on the locale) wherever the movement operates to spread awareness about their local initiatives.

So far, he’s already visited Red Cross societies in 189 countries — a feat that Pedersen says has never been done before.

And of course, the cardinal rule: no flights. With the ease of airports off the table, he’d need to traverse the globe via trains, taxis, buses, ride-shares, tuk-tuks, ferries and container ships.

Pedersen has relied heavily on cargo ships to travel long distances, working closely with companies such as Maersk, Blue Water Shipping, Swire, MSC, Pacific international Lines, Neptune and Columbia.

“You can’t just show up and get on a container ship,” says Pedersen. “You need to get approvals from the company ahead of time, which takes a lot of time and patience.”

In some cases, Pedersen relied on his professional connections. In others, his association with the Red Cross helped, while the monumental nature of this challenge helped to cement partnerships.

“Coordinating everything takes a lot of time. And even if you do have all your connections planned and everything lined up, you can’t plan for natural disasters or typhoons,” which he says threw his schedule off course on numerous occasions.

Even so, he’s kept all of his promises to himself and his thousands of online followers who have become invested in his journey.

“There’s nothing stopping this journey from ending, except for me … But I have to ask myself: Do I want to be the person who quit? Or do I want to be able to say that I never quit, not even once. Not when I had malaria. Not when I was losing my girlfriend. Not when my grandmother died. Not when I lost financial backing. Not when I was in pain,” he says.

“By completing this project, I’m telling people you can achieve any objective if you just keep working at it.”

Finding a way in

No flights: With the ease of air travel off the table, he’s traversing the globe via trains, taxis, tuk-tuks, ferries and container ships.

Torbjørn (Thor) Pedersen/Once Upon A Saga

Though Pedersen’s Danish passport is one of the most powerful in the world in terms of the access it offers, many visas have still been challenging to secure, especially in notoriously hard-to-visit destinations such as Yemen, Iraq, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Nauru and Angola.

It took more than three weeks to obtain a visa for Iran and nearly three months for Syria, which he secured with help from the Red Cross.

Eventually, he crossed the border to get to Damascus, the capital of Syria. Due to conflicts in the region at the time, he then had to find his way to Jordan on a container ship via the Gulf of Aqaba, which meant backtracking through Lebanon and Egypt.

“So it took a loop to get to Jordan, and it’s been like that a few times. If you’re going without flying, then you’re really locked into the countries that are surrounding you. And you need to plan it well.”

In many cases, bureaucracy made the processes all the more excruciating. At the land border with Angola, for example, he was turned away at first because he didn’t speak native French.

Then they rejected his application because he used the wrong color pen. When he refiled his forms, his passport photo was wrong. He got new passport photos, but then his invitation letter was not clear enough.

Each rejection cost him weeks.

“Some of these situations were really Kafka-esque. It took so much time and lots of help from other people,” says Pedersen.

The globetrotter has been giving motivational talks at corporations throughout his travels, which has helped with making influential connections.

“In some cases, CEOs with some power helped me. Other times, I talked with the consulate or got help from friends.

“Whenever I needed help someone reached out and helped me. But I always figured out a solution — and I did it the right way. I never offered a single bribe.”

A rash decision

While Pedersen is usually meticulous about planning, an episode in Cameroon sent him spiraling.

After spending multiple days jumping through hoops to enter neighboring Gabon, Pedersen could not take it anymore.

“People didn’t understand what I was doing. I wanted to give up and just go home, thinking ‘Why the heck am I even doing this? What’s in it for anyone at this point?’ I kind of lost it.”

He made a rash decision to try another crossing, which required an 800-kilometer drive on dusty dirt roads in the middle of the night.

At 3 a.m., a pair of headlights flashed ahead. Three uniformed men walked into the street, waving their rifles, and demanded Pedersen and his taxi driver get out of the car.

“They were armed to their teeth and drunk out of their minds. That’s just a no-go situation,” he recalls.

“My heart dropped. This is it. This is the end of my life. If my life ends there, they toss me in the forest, ants and animals will eat me in no time, no one will ever know. I hadn’t told anyone I was going to do this.”

He waited in this state of terror for 45 minutes as the men intimidated him with their rifles, fingers on triggers. Then, for no reason whatsoever, they let him go.

“We just got out of there like bats out of hell.”

Months of great memories

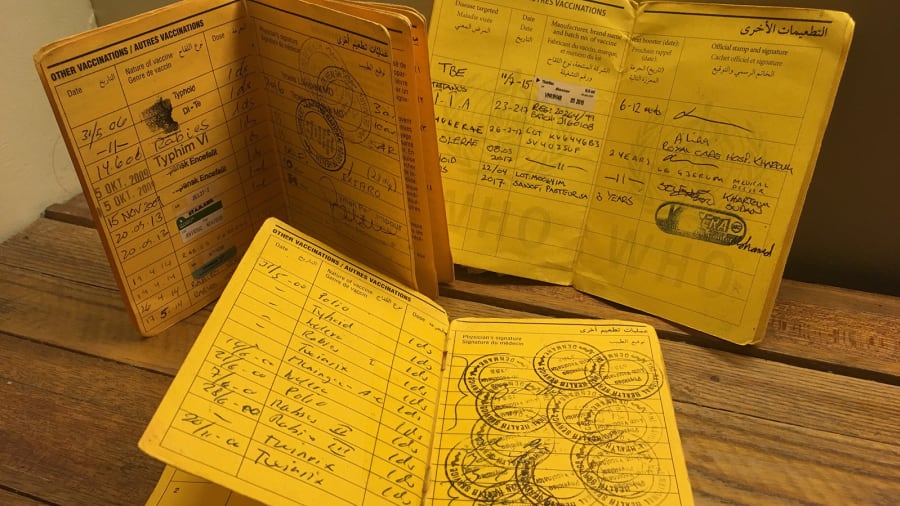

Visiting every Red Cross: Pedersen visits the Red Cross wherever the movement operates to spread awareness about their local initiatives. So far, he’s already visited Red Cross societies in 189 countries — a feat that’s never been done before, he says.

Torbjørn (Thor) Pedersen/Once Upon A Saga

As he attempts the impossible task of summarizing six and a half years into a highlight reel, Pedersen tells me that the positive memories dramatically outnumber the bad.

“We’d be talking for a couple of days if I were to tell you about all of the bad things that happened. But we’d need months to cover all the good things — that’s the balance.”

In Hong Kong, for instance, Pedersen has encountered incredible hospitality during the global pandemic.

A family living in Sai Kung, about an hour northeast of Central, invited him to stay in their spare guest room for a few days.

That was before the world ground to a halt. It’s been 86 days, and they insist he’s welcome to stay as long as it takes.

Pedersen encountered similar warmth and generosity while marooned in the Solomon Islands, where a typhoon near Japan delayed his container ship.

He decided to use the extra days to explore the Western Province. While Pedersen was riding alone on a ferry, an elderly man invited him to an island called Vori Vori to experience life in his village.

A few days later, Pedersen took a ferry then a small motorized canoe to the remote island, which is home to about 100 people.

“There is no running water, no electricity, just a generator if they absolutely needed to power something. They catch the fish they eat every day, they have plenty of coconuts, you can bathe in the stream. It’s an amazing place.”

When the village elder learned Pedersen had a laptop, he asked if the residents could watch a movie.

That night, they powered up the generator and nearly 80 people huddled around Pedersen’s computer to watch 1998 war drama “The Thin Red Line,” which is set in the Solomon Islands.

“You can’t plan that experience. You can’t buy that. It was just astonishing,” says Pedersen.

And then there’s the world’s natural beauty, which has left him speechless on countless occasions.

While crossing the North Atlantic on a container ship to reach Canada, they hit a terrible storm. For four days, the ship heaved in the wind.

“It was chaos. I thought we were going to sink and die. But when the storm passed, the water was like dark blue oil, so still and smooth. I have never seen an ocean like that.”

The only interruptions in the glass-like surface were animals — whales came up to breathe, dolphins jumped and played. And to cap it off, that night the skies cleared and the Northern Lights danced overhead.

Late in the journey, about half a day before they reached Canada, powerful gusts of wind swept the distinct aroma of trees and pollen across the ship’s deck.

“Suddenly, you could smell trees in a very powerful way. It was as if I were standing in the forest. So after 12 days of smelling oil, metal and the ocean, suddenly we could smell Canada before we could see it.”

The finish line

Staying positive’: “Today, the world might be falling apart,” says the adventurer. “But, next month, the sun will be shining on my face.”

Torbjørn (Thor) Pedersen/Once Upon A Saga

When looking at the sheer distance he’s covered — more than 300,000 kilometers — Pedersen has now circled the globe seven times in the past 6.5 years.

He’s reached 194 countries, with just nine to go: Palau, Vanuatu, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, New Zealand, Australia, Sri Lanka and the grand finale in Maldives.

When he reaches Maldives, he’s planning a celebration with his fiancé and fellow globetrotters, such as Lexi Alford, who is the youngest person to visit every country in the world, and Gunnar Garfors, one of the few people to have visited every country twice.

He’s can’t wait to see his fiancé, who he was planning to marry in New Zealand before the pandemic froze the globe.

“My fiancé has been incredibly supportive during this whole process,” says Pedersen. “She’s been out to visit me 21 times.

“Actually, there’s a running joke-slash-tradition: I only shave it off when she comes out to see me!” he says of his impressive beard. “I haven’t seen her now for seven months, so that’s why it’s this long.”

By Pedersen’s estimation, even if he can finally get to Palau this summer, the remainder of his journey will take at least another 10 months to a year.

“It would be easy to just go to the airport and fly home. Sometimes I think about it. But at some point, this project stopped being about me, and started being about other people.”

At its heart, he says, this is not a travel project but a people project. His primary mission is to shed light on the inherent goodness of people, on how much we have in common — not our differences.

“People are almost always amazing. We all care about the same things: our families, our jobs, education, ‘Game of Thrones.’ We all like good food. We like to dance. We like to relax, we like to laugh … highlighting these similarities is a big part of my purpose.”

There are also many people depending on him to finish, in one way or another.

Over the years, he’s received numerous private messages from people who have been inspired by his determination to persist in their own lives, from job-hunting to weight loss, to studying, learning a new language, or getting out of bed after losing a loved one.

“Again, and again, I’ve told the people who follow this project that we will get to the other side,” he says.

“Today, the world might be falling apart. But, next month, the sun will be shining on my face. We made it on that ship, we got that visa, we crossed the border … we did the impossible.”

Reporting by Kate Springer, CNN