Already recognized as one of the leading public health threats facing humanity today, it is feared that a warming world is making it harder to stop the insidious spread of drug-resistant superbugs.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which the World Health Organization has referred to as the “silent pandemic,” is an often overlooked and growing global health crisis.

The United Nations health agency has previously declared AMR to be one of the top 10 global threats to human health and says an estimated 1.3 million people die every year directly due to resistant pathogens.

That figure is on track to “soar dramatically” without urgent action, the WHO says, leading to higher public health, economic and social costs and pushing more people into poverty, particularly in low-income countries.

Antimicrobials, which include life-saving antibiotics and antivirals, are medicines used to prevent and treat infections in humans and animals. Their overuse and misuse, however, is known to be the chief driver of the AMR phenomenon.

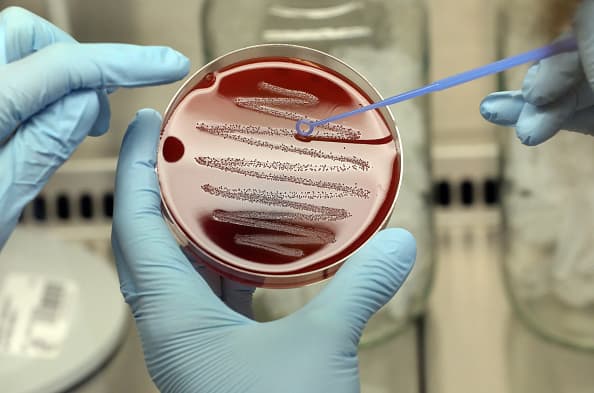

AMR occurs when microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites develop the ability to persist or even grow despite the presence of drugs designed to kill them.

Making matters worse, research has shown that climate change is exacerbating the AMR crisis in several ways.

“Climate change is intrinsically important because of what’s going on with our planet and the problem is that the more our temperatures rise, the more infectious diseases can transmit — and that includes AMR bacteria,” Tina Joshi, associate professor of molecular microbiology at the U.K.’s University of Plymouth, told CNBC via videoconference.

“AMR bacteria is known as a silent pandemic. The reason its known as silent is that no one knows about it — and it’s really sad that no one seems to care,” Joshi said.

A ‘completely broken’ diagnostics pipeline

A report published by the UN Environment Program earlier this year, entitled “Bracing for Superbugs,” illustrates the role of the climate crisis and other environmental factors in the development, spread and transmission of AMR.

These include higher temperatures being associated with the rate of the spread of antibiotic resistant genes between microorganisms, the emergence of AMR due to the continuing disruption of extreme weather events and increased pollution creating favorable conditions for bugs to develop resistance.

Scientists said earlier this month that an extraordinary run of global temperature records means 2023 is “virtually certain” to be the warmest year ever recorded. Extreme heat is fueled by the climate crisis, which makes extreme weather more frequent and more intense.

It kind of boils down to the fact that it’s not economically viable to actually invest in antibiotics and their development. And that is something that is rocking the antimicrobial world.Tina Joshiassociate professor of molecular microbiology at the University of Plymouth

Robb Butler, director of the division of communicable diseases, environment and health at WHO Europe, described AMR as “an extremely pressing global health challenge.”

“It’s a huge health burden and it costs just the EU member states somewhere in the region of 1.5 billion euros ($1.6 billion) per annum in health costs but also in loss of productivity. So, it’s a phenomenal challenge,” Butler told CNBC via telephone.

Butler said he hoped the upcoming COP28 climate conference in the United Arab Emirates could provide a platform for international policymakers to start to recognize the association between the climate crisis and AMR. The UAE will host the U.N.’s annual climate summit from Nov. 30 through to Dec. 12.

“The problem is that, of course, antibiotics or antimicrobials, are not that attractive for industry to develop. They are expensive, they are high-risk — and we haven’t seen over the last 20 years antimicrobial drugs developed with enough unique characteristics to avoid resistance.”

“We hear people talking about this ‘silent pandemic,’ but it shouldn’t be silent. We should be making more noise about it,” Butler said.

“You would imagine the [coronavirus] pandemic could have been a wake-up call, but we still don’t see enough attention to AMR.”

Butler said that perhaps his biggest concern was how to incentivize industry leaders to tackle AMR at a time when they are fully aware they may be better off investing in other research and development areas — such as producing a highly profitable obesity drug, for example.

“For me, that’s the one that keeps me awake at night,” Butler said. “I can think about how society might change through shocks to more prudently use antibiotics so that we don’t build resistance to antibiotics. But if there is absolutely nothing in the pipeline with innovative characteristics then we’ve kind of lost,” he added. “And that really, really concerns me.”

The University of Plymouth’s Joshi echoed this view, describing the AMR diagnostics pipeline as “completely broken” and calling for policymakers to urgently reinvigorate this process.

“It’s not profit-making,” she added. “It kind of boils down to the fact that it’s not economically viable to actually invest in antibiotics and their development. And that is something that is rocking the antimicrobial world.”

The next pandemic?

Thomas Schinecker, chief executive of the Swiss pharmaceutical company Roche, said last month that policymakers were in danger of failing to learn the necessary lessons from the coronavirus pandemic — adding that this could have serious ramifications for the AMR health crisis.

“I don’t believe that we have learned the lessons that we should have learned in the last pandemic, and I don’t think we are better prepared for the next pandemic,” Schinecker told CNBC’s “Squawk Box Europe” on Oct. 19.

“I think it is important that we take those learnings, that we implement what we need to do to be prepared because the next pandemic will come,” he continued.

“One of the concerns I have is that potentially antibiotic resistant bacteria could be that pandemic. With that, we need to focus on preparing for such situations in the future.”

Source: CNBC