WASHINGTON — Two days after national security advisor Jake Sullivan warned his Chinese counterpart of serious consequences if Beijing helps Russia wage its war against Ukraine, what exactly they might be remains shrouded in secrecy.

“We’re going to have this conversation directly with China and Chinese leadership, not through the media,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki told reporters on Tuesday.

Psaki said that Sullivan was “very direct about the consequences” during his Monday meeting in Rome with China’s top foreign policy official, Yang Jiechi.

“But in terms of any potential impacts or consequences, we’ll lead those through private diplomatic channels at this point,” Psaki said.

As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine approaches its fourth week, concerns over how Western allies will react if China or Chinese companies try to assist Moscow in evading sanctions imposed by the U.S., U.K. and Europe have added a new level of uncertainty to global markets already reeling from the collapse of the Russian economy.

That uncertainty is compounded by the fresh memory of what happened the last time the White House issued vague warnings about consequences, during the lead-up to Russia’s invasion.

On Feb. 20, four days before Russian troops marched into Ukraine, Psaki issued a statement saying the U.S. was “ready to impose swift and severe consequences” if Russian carried out its apparent plans.

At the time, few analysts believed the United States and Europe could actually reach consensus on the most severe sanctions under consideration — like freezing Russia’s central bank reserves. But they did, catching both Moscow and Wall Street off guard.

When it comes to China, no one wants to make the same mistake again.

Moscow has reportedly asked Beijing for military and economic assistance to wage its war against Ukraine, although both governments publicly deny it.

But China has little interest in becoming embroiled in the economic battle between Moscow and the rest of the developed world.

“China is not a party to the crisis, nor does it want the sanctions to affect China,” foreign minister Wang Yi said during a phone call Monday with Spain’s foreign minister, Jose Manuel Albares.

Still, Wang insisted that “China has the right to safeguard its legitimate rights and interests,” according to an official notice of the call from Beijing.

In the past week, it has become increasingly clear that the Kremlin views Beijing as an economic lifeline.

Russian finance minister Anton Siluanov said Sunday that his country’s economic “partnership with China will still allow us to maintain the cooperation that we have achieved … but also increase it in an environment where Western markets are closing” to Russian exports.

This “increased” cooperation from China could take several different forms. Some of them would overtly violate sanctions against Russia, triggering an automatic responses from the U.S. But experts say other actions Beijing might take would be technically legal, forcing the U.S. to rely more on soft power tactics to counter them.

Overt violations could include helping Russia get around U.S. export controls on high-tech equipment by purchasing American products and then selling them to Moscow.

That move would be very risky for businesses, however. The sanctions are specifically written to apply not only to American companies, but to any company in the world that uses U.S. software or components, which includes many in China.

Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo recently explained what the consequences would be for a major Chinese semiconductor company, if the U.S. learned it was selling chips to Russia in violation of American export controls.

“We could essentially shut [the company] down, because we prevent them from using our equipment and our software,” Raimondo said in an interview with The New York Times on March 8.

Raimondo’s example highlights how the U.S. can leverage its economic power to make any company’s decision to help Russia evade sanctions, essentially, a fatal one.

“Most large institutions in China are not willing to take the risk of falling afoul of U.S. sanctions, and so any sanction busting is likely to be done by smaller institutions that have less to lose,” said Martin Chorzempa, a research fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“Overall, China looks like it’s going to complain but comply,” he told The Washington Post.

Another possible avenue for cooperation between Russia and China would be for Beijing to buy Russian oil and gas on the cheap, Alexander Gabuev, senior fellow and Russia chair at the think tank Carnegie Moscow Center, told CNBC’s “Capital Connection” on Monday.

“There will be no formal violation of U.S. and EU sanctions, but that will be a significant material lifeline to the regime” in Russia, Gabuev said.

That kind of Sino-Russian cooperation demands a different response from the United States, working together with European allies to emphasize the long-term risk to China’s reputation on the world stage.

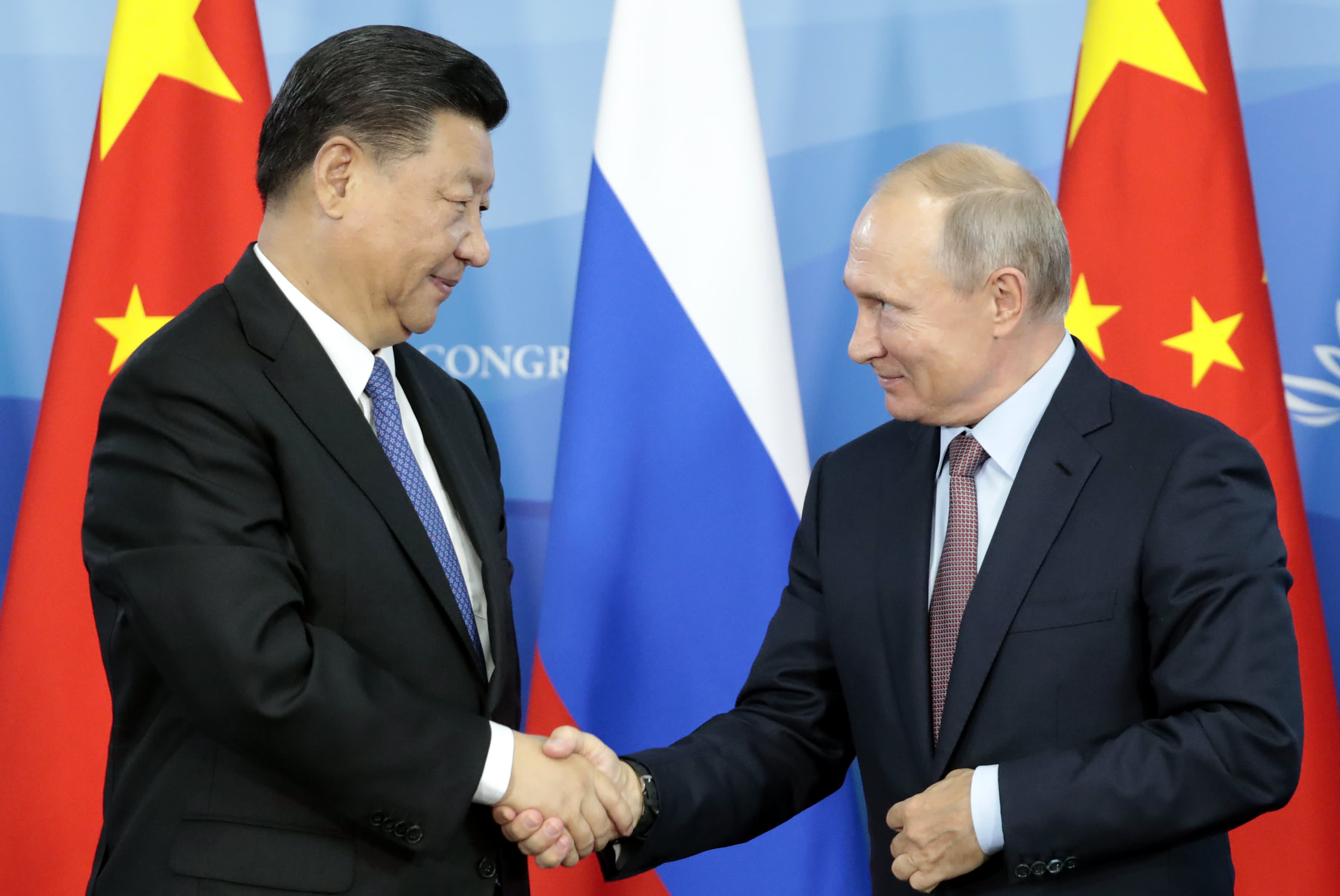

“[Russian President] Vladimir Putin is … the bad guy in the eyes of the world” and Moscow is fast becoming a “pariah state,” said Robert Daly, director of the Kissinger Institute on China and the U.S.

“Russia, Cuba, North Korea, Venezuela, Iran — this isn’t really the international club that most Chinese people aspire to be part of,” Daly said on CNBC’s “Squawk Box Asia” on Tuesday.

As civilian casualties in Ukraine mount and TVs around the world broadcast images of bombed out residential areas and brave Ukrainian resistance fighters, “circumstances are pushing China further in that direction,” said Daly.

But that doesn’t mean the country will break with its longtime ally. Instead, Beijing can be expected to be “religious about observing” the U.S. and EU sanctions but do “everything possible” to help Moscow, Gabuev said.

— CNBC’s Eustance Huang and Weizhen Tan contributed reporting.

Source: CNBC